Spatial Randomness and Autocorrelation

An introduction to computing spatial Randomness and autocorrelation in R with examples

Background

Spatial randomness and spatial autocorrelation are two concepts related to the distribution of data in space. They describe different aspects of spatial data and have different implications for the analysis of spatial patterns.

Definitions

Spatial randomness: Spatial randomness refers to a situation where the location of events or features in space does not follow any discernible pattern. In other words, the events or features are randomly distributed across the study area, and their locations are not influenced by the locations of other events or features. Complete spatial randomness (CSR) is often used as a null hypothesis in spatial analyses, which assumes that the observed pattern is random and not influenced by any underlying spatial process.

Spatial autocorrelation: Spatial autocorrelation refers to the correlation between a variable at one location and the same variable at neighboring locations. It measures the degree to which nearby locations exhibit similar (or dissimilar) values. Positive spatial autocorrelation means that similar values are clustered together, while negative spatial autocorrelation means that dissimilar values are closer together. If there is no spatial autocorrelation, the values are randomly distributed across the study area.

Differences

-

Spatial randomness pertains to the absence of any discernible pattern in the distribution of events or features in space, while spatial autocorrelation measures the correlation between a variable at one location and the same variable at neighboring locations.

-

Spatial randomness is often used as a null hypothesis in spatial analysis, while spatial autocorrelation is an inherent property of the data that can reveal underlying spatial processes or structures.

In summary, spatial randomness and spatial autocorrelation describe different aspects of spatial data. Spatial randomness relates to the distribution of events or features, while spatial autocorrelation quantifies the degree of similarity between values at nearby locations. These concepts are essential for understanding and analyzing spatial patterns in various types of spatial data.

Complete Spatial Randomness (CSR) measurements

-

Ripley's K function: The K function is used to assess CSR in point patterns. It calculates the expected number of points within a given distance ‘r’ of an arbitrary point, divided by the overall point density. If the observed K function is close to the theoretical K function under CSR, the point pattern is consistent with spatial randomness. -

L function: The L function is a derived function from Ripley’s K function, which is used to assess Complete Spatial Randomness (CSR) in point pattern data. The L function is designed to provide a linearized visualization of the K function, making it easier to interpret the results. -

Nearest Neighbor Distance Distribution function (G function): The G function is another measure used to assess CSR in point patterns. It estimates the cumulative distribution function of the nearest neighbor distances in a point pattern. If the observed G function is close to the theoretical G function under CSR, the point pattern is consistent with spatial randomness.

Spatial autocorrelation measurements

-

Moran's IMoran’s I is a global measure of spatial autocorrelation for continuous or areal data. It measures the correlation between a variable at one location and the same variable at neighboring locations. Moran’s I values range from -1 (negative spatial autocorrelation) to 1 (positive spatial autocorrelation), with values close to 0 indicating no spatial autocorrelation. -

Geary's C: Geary’s C is another global measure of spatial autocorrelation for continuous or areal data. It is based on the difference between values at neighboring locations. Geary’s C values range from 0 (positive spatial autocorrelation) to 2 (negative spatial autocorrelation), with values close to 1 indicating no spatial autocorrelation. -

Local Indicators of Spatial Association (LISA): LISA is a set of local measures of spatial autocorrelation for continuous or areal data. It identifies local clusters of high or low values and spatial outliers. Common LISA statistics include Local Moran’s I, Local Geary’s C, and Local Getis-Ord G*. -

Semivariogram: The semivariogram is a measure of spatial autocorrelation for continuous data that quantifies the similarity between pairs of data points as a function of the distance between them. It is used to model spatial dependence and is the basis for geostatistical techniques like kriging.

Examples of CSR

Using K Function and L Fuction

The K function is defined by:

\[K(r) = λ^{-1} * E[N(r)] \quad\quad (1)\]where λ is the point density (total number of points divided by the study area), E[N(r)] is the expected number of points within distance ‘r’ from an arbitrary point, and r is the distance.

When analyzing point patterns to test for CSR, we often assume an underlying Poisson process.The theoretical K function under CSR for a Poisson process is:

\[K(r) = \pi * r^2 \quad\quad (2)\]-

If the observed K function is close to the theoretical K function (Poisson process), the point pattern is consistent with CSR.

-

If the observed K function lies above the theoretical K function, the point pattern exhibits clustering.

-

If the observed K function lies below the theoretical K function, the point pattern exhibits regularity or dispersion.

By comparing the observed K function with the theoretical K function under the CSR assumption, you can assess whether the spatial distribution of points is consistent with a Poisson process or if there is evidence of clustering or regularity in the data.

When working with a sample of data points, the K function will not usually be known, and we will use the Edge-corrected estimation of K function (Ripley’s K function):

\[K(r) = \left(1 / λ\right) * \sum_{i=1}^{n}\left[\sum_{j\neq i}(I(||u_i - u_j|| <= r) / w(||u_i - u_j||))\right] \quad\quad (3)\]where:

- K(r) is the estimated K function at distance r,

- λ is the point density (total number of points divided by the study area),

- n is the total number of points in the point pattern,

- $u_i$ and $u_j$ are the spatial coordinates of points i and j, respectively,

- $||u_i - u_j||$ is the Euclidean distance between points i and j,

- I(·) is an indicator function that equals 1 if the condition inside the brackets is true and 0 otherwise,

- w(·) is an edge-correction function that accounts for the fact that points near the boundary of the study area have fewer neighbors.

The edge correction function is an essential component of Ripley’s K function estimation. It is needed to account for the boundary effects that arise when analyzing point patterns within a finite study area. Points near the boundary of the study area have fewer neighbors than points located in the interior, which can lead to biased estimations of the K function. Note that there are different edge-correction methods available, such as the isotropic correction, which is the default method in Ripley’s K function estimation. The isotropic correction is given by:

\[w(||u_i - u_j||) = 1/(1 - (π * r^2 / A)) \quad\quad (4)\]The L function is derived from the K function and is used to provide a linearized interpretation of the results from the K function. The L function is defined as:

\[L(r) = \sqrt{\frac{K(r)}{\pi}} \quad\quad (5)\]Given a Poisson process, we can substitute Equation 2 into the L function to get the L function under CSR:

\[L_{CSR}(r) = \sqrt{\frac{\pi r^2}{\pi}} = r \quad\quad (6)\]To simplify the interpretation of the L function, we often plot the difference between the L function and the distance r:

\[L(r) - r \quad\quad (7)\]The relationship between the K function and the L function can be summarized as follows:

-

The L function is derived from the K function to provide a linearized interpretation of the spatial pattern analysis.

-

The L function under CSR is equal to the distance r, which simplifies the interpretation of the results.

-

By plotting the difference between the L function and the distance r, we can easily identify deviations from CSR, clustering, or dispersion.

To interpret the L(r) - r plot:

-

If the L(r) - r plot is close to the horizontal axis (L(r) - r ≈ 0), it suggests Complete Spatial Randomness (CSR).

-

If the L(r) - r plot lies above the horizontal axis (L(r) - r > 0), it indicates clustering.

-

If the L(r) - r plot lies below the horizontal axis (L(r) - r < 0), it indicates regularity or dispersion.

In summary, the L function is derived from the K function to provide a more straightforward interpretation of spatial patterns in point data. By comparing the L function plot with the expected L function under CSR (L(r) = r), we can assess the degree of clustering or regularity in the data.

In the following example, we will use Ripley’s K function to analyze the bramblecanes dataset from the spatstatlibrary in R. First, Let us visulize the locations of the bramble canes being analysed.

Figure 1: Bramble Cane Locations

Next, we will extimate and plot the observed K function along with the theoretical K function under CSR

K_hat <- Kest(bramblecanes)

plot(K_hat, main = "Observed K Function vs. Theoretical K Function (CSR)")Besides of the isotropic correction mentioned in Equation 4, Kest by defualt outputs results using the other three edge correction below:

-

Border correction: The border edge correction method adjusts the K function estimate by taking into account the distance between the points and the study region’s boundary. It assumes that the point pattern’s intensity is constant up to the boundary, and beyond the boundary, it drops to zero. The border method is suitable when the study region’s boundary is irregular or complex. The border method works by applying a correction factor to the K function estimates, which is based on the distance of each point to the nearest point on the boundary.

-

Translation correction: The translate edge correction method adjusts the K function estimate by translating the point pattern to several random locations and averaging the K function estimates obtained from each translation. This method assumes that the point pattern is homogeneous and isotropic, meaning that the intensity and orientation of the point pattern are the same throughout the study region. The translate method is suitable for rectangular or square-shaped study regions with uniform boundaries.

-

Periodic correction: The periodic edge correction method adjusts the K function estimate by creating periodic copies of the study region and the point pattern. This method assumes that the point pattern is periodic and that the study region’s shape and size repeat indefinitely in all directions. The periodic method works by creating multiple copies of the point pattern and the study region, shifting each copy by a multiple of the study region’s size, and then computing the average of the K function estimates obtained from each copy.

Figure 2: Obeserved K Function vs Theoretical K function (CSR)

Finally, we can compute and plot the L function:

L_hat <- Lest(bramblecanes)

plot(L_hat, main = "L Function: L(r) - r")Figure 3: Obeserved L Function vs Theoretical L function (CSR)

Using G Function

The G function, also known as the nearest-neighbor distance distribution function, is defined as the cumulative distribution function of the nearest-neighbor distances between points in the point pattern.

The equation for the G function is:

\[G(r) = \frac{1}{n} \sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{j\neq i}^{n}I(d(x_i,x_j) \leq r)\]where G(r) is the value of the G function at distance r, n is the number of points in the point pattern, I() is the indicator function that takes the value 1 if the distance between the ith and jth points in the point pattern is less than or equal to r, and 0 otherwise, and $d(x_i,x_j)$ is the Euclidean distance between the ith and jth points in the point pattern.

In other words, the G function calculates the proportion of points in the point pattern that have at least one nearest neighbor within distance r. The G function can be used to test for spatial clustering or regularity in a point pattern. If the G function values are above or below the expected values under CSR, this suggests clustering or regularity, respectively.

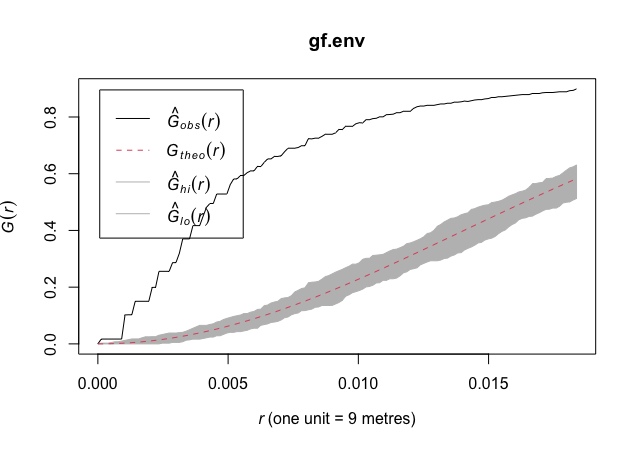

We can use the envelope function to construct the upper and lower bounds of the expected values of the Gest function under CSR. The envelope function is calculated by repeatedly simulating CSR point patterns within the study region and calculating the G function for each simulated pattern. The envelope function is then constructed by calculating the upper and lower percentiles of the simulated G function values for each distance. The resulting upper and lower envelopes are used to compare the observed Gest function values with the expected values under CSR.

gf.env <- envelope(bramblecanes, Gest, correction = "border")

plot(gf.env)Figure 4: Obeserved G Function vs Theoretical G function with Envelope (CSR)

Example of Moran’s I

The Pennsylvania Lung Cancer Data

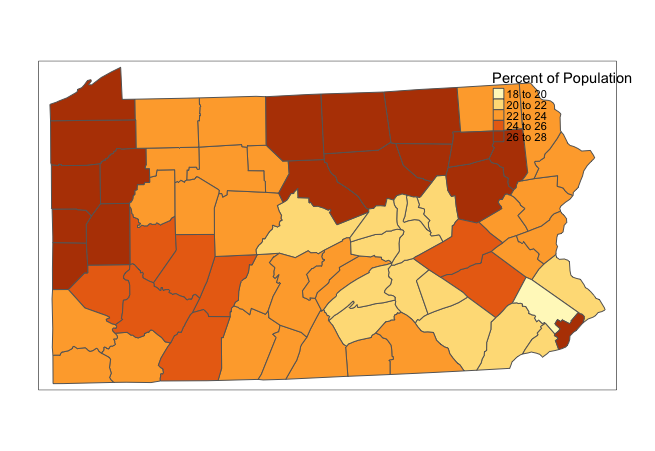

The spatialepi package in R contains several datasets related to the spatial analysis of epidemiological data. One of these datasets is the pennLC dataset, which contains information on lung cancer incidence rates in Pennsylvania by county in 2002.

# Make sure the necessary packages have been loaded

library(tmap)

library(tmaptools)

library(SpatialEpi)

library(sf)

# Read in the Pennsylvania lung cancer data

data(pennLC)

# Extract the SpatialPolygon info

penn.state.latlong <- pennLC$spatial.polygon

# Convert to UTM zone 17N

penn.state.latlong<- st_as_sf(penn.state.latlong)

penn.state.utm <- set_projection(penn.state.latlong, 3724)

if ("sf" %in% class(penn.state.latlong))

penn.state.utm <- as(penn.state.utm, "Spatial")

# Obtain the smoking rates

penn.state.utm$smk <- pennLC$smoking$smoking*100

# Draw a choropleth map of the smoking rates

tm_shape(penn.state.utm) + tm_polygons(col="smk", title="Percent of Population")Figure 5: Pennsylvania Smoking Rates

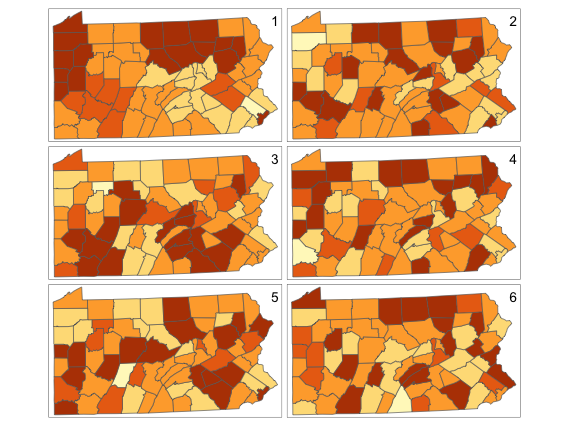

# Set up a set of five 'fake' smoking update rates as well as the real one

# Create new columns in penn.state.utm for randomised data

# Here the seed 4676 is used. Use a different one to get an unknown outcome.

set.seed(4676)

penn.state.utm$smk_rand1 <- sample(penn.state.utm$smk)

penn.state.utm$smk_rand2 <- sample(penn.state.utm$smk)

penn.state.utm$smk_rand3 <- sample(penn.state.utm$smk)

penn.state.utm$smk_rand4 <- sample(penn.state.utm$smk)

penn.state.utm$smk_rand5 <- sample(penn.state.utm$smk)

# Scramble the variables used in terms of plotting order

vars <- sample(c('smk','smk_rand1','smk_rand2','smk_rand3','smk_rand4','smk_rand5'))

# Which one will be the real data?

# Don't look at this variable before you see the maps!

real.data.i <- which(vars == 'smk')

# Draw the scrambled map grid

tm_shape(penn.state.utm) +

tm_polygons(col=vars, legend.show=FALSE) +

tm_layout(title= 1:6, title.position=c("right","top"))Visual Explotration of Autocorrelation

Figure 6: Randomized Pennsylvania Smoking Rates

Moran’s I is calculated using the formula:

\[I = \frac{n}{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{j=1}^{n}w_{ij}} \frac{\sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{j=1}^{n}w_{ij}(x_i - \bar{x})(x_j - \bar{x})}{\sum_{i=1}^{n}(x_i - \bar{x})^2}\]where $n$ is the number of observations, $w_{ij}$ is the spatial weight between observation $i$ and observation $j$, $x_i$ is the value of the variable of interest for observation $i$, and $\bar{x}$ is the mean value of the variable of interest.

The first term in the formula represents the spatial scale of analysis, or the effective number of neighboring observations. It is equal to $n$ divided by the sum of the spatial weights matrix $W$, which represents the total number of neighboring observations across all observations.

The second term in the formula represents the spatial autocovariance of the variable of interest. It is calculated as the sum of the product of the spatial weight $w_{ij}$ between each pair of observations $i$ and $j$, and the difference between the variable value $x_i$ for observation $i$ and the mean value $\bar{x}$ of the variable across all observations, and the same difference for observation $j$. This term quantifies the degree to which similar values of the variable tend to be clustered together in space.

The third term in the formula represents the overall variance of the variable of interest. It is calculated as the sum of the squared difference between the variable value $x_i$ for each observation $i$ and the mean value $\bar{x}$ of the variable across all observations. This term represents the total amount of variation in the variable across all observations.

To calculate the spatial weights $w_{ij}$ for Moran’s I, there are several methods available, but the most common ones include the following:

- Binary contiguity: In this method, two observations are considered neighbors if they share a common boundary or vertex in a spatial domain. The spatial weight $w_{ij}$ is set to 1 if observation $i$ and $j$ are neighbors, and 0 otherwise.

- Distance-based weights: In this method, spatial weights are calculated based on the distance between observations. The spatial weight $w_{ij}$ is set to a decreasing function of the distance between observation $i$ and $j$, such that observations that are closer together have a higher weight than those that are farther apart.

where $d_{ij}$ is the Euclidean distance between observations $i$ and $j$, and $p$ is a positive constant that controls the rate of decrease of the weight with distance.

- K-nearest neighbor weights: In this method, the spatial weight $w_{ij}$ is set to 1 if observation $j$ is one of the k-nearest neighbors of observation $i$, and 0 otherwise.

- Kernel weights: In this method, spatial weights are calculated based on a continuous function that assigns weights to all observations in the study area, depending on their distance from the focal observation $i$. The spatial weight $w_{ij}$ is set to the value of the kernel function evaluated at the distance between observation $i$ and $j$.

where $K$ is the kernel function, $d_{ij}$ is the Euclidean distance between observations $i$ and $j$, and $h$ is a positive constant that controls the bandwidth of the kernel. Commonly used kernel functions include the Gaussian, uniform, and triangular kernels.

- Lagged mean weights: In this method, spatial weights are calculated based on the average value of the variable of interest for neighboring observations. The spatial weight $w_{ij}$ is set to the ratio of the deviation of the value of observation $j$ from the mean of all neighboring observations of observation $i$, divided by the variance of the variable.

where $x_j$ is the value of the variable for observation $j$, $\bar{x}_{N_i}$ is the mean value of the variable for all observations in the neighborhood of observation $i$ (excluding observation $i$ itself), and $N_i$ is the set of neighbors of observation $i$. This method accounts for spatial autocorrelation in the variable of interest by estimating the local variance of the variable based on neighboring observations.

Note that the lagged mean method assumes that the relationship between neighboring observations is linear and stationary. It may not be appropriate for non-linear or non-stationary

require(spdep)

# Calculate spatial weights matrix

nb <- poly2nb(penn.state.utm, queen=TRUE)

W <- nb2listw(nb)

# Calculate Moran's I for smoking rates

moran <- moran.test(penn.state.utm$smk, listw=W)

# Print Moran's I results

cat("Moran's I for smoking rates:", moran$estimate[1], "\n")

cat("p-value:", moran$p.value, "\n")