Kriging Interpolation in R

An introduction to working with kriging in R with examples

Introduction

Spatial interpolation techniques are used to estimate the values of variables at unsampled locations based on the values of the same variable at sampled locations. One of the popular spatial interpolation techniques used in geostatistics is Kriging interpolation. Kriging interpolation is a powerful statistical method that allows one to predict the values of variables at unsampled locations while also accounting for spatial autocorrelation.

In this tutorial, we will go through the basic concepts of Kriging interpolation, the types of Kriging, and how to implement the method in R using the gstat library.

Basic Concepts

Kriging is based on the assumption that the spatial correlation between observations decreases with distance, and that this correlation can be modeled using a mathematical function.

The basic idea of kriging is to find a set of weights that can be used to combine the observed values at nearby locations to estimate the value at the target location. The weights are chosen to minimize the variance of the estimation error, subject to the constraint that the estimated value is a linear combination of the observed values.

The kriging estimator can be written as:

\[\hat{Z}(s_0)=\sum_{i=1}^n \lambda_i Z(s_i) \quad\quad (1)\]where \(\hat{Z}(s_0)\) is the estimated value at the target location s, \(Z(s_i)\) is the observed value at location i, \(\lambda_i\) is the weight assigned to the observed value at location i, and \(n\) is the number of observed locations.

The weights are typically chosen to minimize the estimation variance \(\sigma^2\), which is given by:

\[min\ \ \ \sigma^2 = E \left[ Z(s_0)-\sum_{i=1}^n \lambda_i Z(s_i) \right] \quad\quad (2)\]The weights \(\lambda_i\) are chosen to minimize the estimation variance subject to the constraint that they sum to one:

\[\sum_{i=1}^n \lambda_i = 1 \quad\quad (3)\]Empirical Semivariogram

Semivariogram is a tool commonly used in geostatistics to analyze spatial autocorrelation in data. It is a measure of the dissimilarity between pairs of values at different locations within a dataset. Semivariogram can provide insights into the spatial structure of data, which can be useful in predicting values at unobserved locations through kriging interpolation.

The empirical semivariogram is defined as the average squared difference between pairs of observations separated by a certain distance or lag, and is expressed mathematically as:

\[\gamma(h) = \frac{1}{2N(h)} \sum_{i=1}^{n} \sum_{|s_j-s_i| < h} [Z(s_i)-Z(s_j)]^2 \quad\quad (4)\]where \(\gamma(h)\) is the semivariance for a lag distance \(h\), \(N(h)\) is the number of pairs of observations separated by the distance \(h\), and \(Z(s_i)\) is the value of the variable at location \(s_i\).

The empirical semivariogram is typically plotted as a function of lag distance, which shows how the dissimilarity between pairs of observations changes as the distance between them increases. The shape of the semivariogram curve can provide insights into the spatial structure of the data.

In kriging interpolation, the semivariogram is used to estimate the spatial autocorrelation of the variable being modeled. The semivariogram model is then used to estimate the variance of the estimation errors \(\sigma^2\) at unobserved locations, which is used to calculate the kriging weights. The kriging weights are then used to calculate the estimated value at the unobserved location.

Modeling Semivariogram

Empirical semivariogram does not assume under underlying spatial structure of the data. In order to use semivariogram for spatial prediction through kriging interpolation or other geostatistical techniques, it is necessary to model the spatial autocorrelation structure of the data using a theoretical semivariogram model.

These models typically have a covariance function that describes the expected correlation between pairs of observations at different distances, based on assumptions about the underlying spatial structure of the data. Table 1 listed some commonly used covariance functions.

Table 1: Some Semivariogram Functions

| Name | Function From |

|---|---|

| Exponential | \(C(h) = c \left[1 - \exp\left(-\frac{h}{a}\right)\right]\) |

| Gaussian | \(C(h) = c \left[1 - \exp\left(-\frac{h^2}{a^2}\right)\right]\) |

| Matérn | \(C(h) = \frac{\sigma^2}{\Gamma(\nu) 2^{\nu-1}} \left(\frac{\sqrt{2\nu}}{a}h\right)^\nu K_\nu\left(\frac{\sqrt{2\nu}}{a}h\right)\) |

| Spherical | \(C(h) = c \left[1.5 \frac{h}{a} - 0.5 \left(\frac{h}{a}\right)^3\right] \quad \text{for } h \le a\) |

Fitting a semivariogram model to the empirical semivariogram involves estimating the parameters of the model, such as the sill, range, and smoothness parameter, that best describe the spatial autocorrelation structure of the data. This is typically done through solving a least-squares problem, where the goal is to minimize the sum of the squared differences between the empirical semivariogram and the semivariogram model predictions at different lag distances.

The following steps outline the basic procedure for fitting a semivariogram model to the empirical semivariogram:

-

Calculate the empirical semivariogram for the dataset using Equation 4.

-

Choose a covariance function that is appropriate for the spatial autocorrelation structure of the data. This can be based on visual inspection of the empirical semivariogram, or on prior knowledge of the data.

-

Estimate the parameters of the semivariogram model. This involves finding the values of the model parameters that minimize the sum of the squared differences between the predicted semivariance values from the model and the observed semivariance values from the empirical semivariogram.

-

Evaluate the goodness of fit of the semivariogram model to the empirical semivariogram. This can be done using various statistical measures, such as the coefficient of determination (\(R^2\)), the root mean squared error (RMSE), or the Akaike information criterion (AIC).

-

Use the fitted semivariogram model to make spatial predictions through kriging interpolation or other geostatistical techniques.

It is important to note that the choice of semivariogram model and the method used for parameter estimation can have a significant impact on the accuracy and reliability of the spatial predictions. It is therefore important to carefully evaluate the performance of different semivariogram models and parameter estimation methods before making spatial predictions.

It is also important to note that the covariance function and the empirical semivariogram are two related concepts in geostatistics, but they are not the same thing. The covariance function describes the relationship between two spatial locations in terms of their similarity or dissimilarity. It is a mathematical function that specifies the covariance or correlation between two locations as a function of their distance or lag. The covariance function is typically used in kriging to estimate the unknown value of a variable at an unsampled location as a linear combination of the observed values at nearby locations, weighted by their covariance with the unsampled location.

The semivariogram, on the other hand, is a measure of spatial dependence or autocorrelation in a variable. It is defined as half the variance of the differences between pairs of values separated by a certain lag or distance. The semivariogram is a graphical representation of the spatial structure of the variable, showing how the similarity between values decreases with increasing distance or lag. The semivariogram is often used in geostatistics to estimate the covariance function, by fitting a model to the empirical semivariogram.

Types of kriging

There are various types of kriging, including ordinary kriging, simple kriging, and universal kriging, which differ in their assumptions about the mean of the unknown variable and the spatial covariance function.

-

Ordinary kriging:

Ordinary kriging assumes that the mean of the unknown variable \(\mu\) is unknown and that the covariance between the variable at any two locations depends only on the distance between the locations (intrisical stationarity). The model assumption can be written as:

\[Z(s) = \mu + \delta(s) \quad\quad (5)\]where \(\delta(s)\) is a zero mean stochastic term, and \(\mu\) is the unknown mean of the variable. For intrinsically stationary process, Equation 2 can be written as (a detailed proof can be found here

\[\sigma^2 = 2\sum_{i=1}^{n}\lambda_i\gamma(s_0, s_i) - \sum_{i=1}^{n}\sum_{j=1}^{n}\lambda_i\lambda_j\gamma(s_i, s_j) \quad\quad (6)\]): Using matrix notation and covariance function \(C(s_i, s_j)\) to model semivariogram \(\gamma(s_i, s_j)\), the kriging system of equations for ordinary kriging can be written as:

\[\begin{bmatrix}C(s_1, s_1) & C(s_1, s_2) & \cdots & C(s_1, s_n) & 1\\C(s_2, s_1) & C(s_2, s_2) & \cdots & C(s_2, s_n) & 1\\\vdots & \vdots& \ddots & \vdots & \vdots\\C(s_n, s_1) & C(s_n, s_2) & \cdots & C(s_n, s_n) & 1\\1 & 1 & \cdots & 1 & 0\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\lambda_1\\\lambda_2\\\vdots\\\lambda_n\\\hat{\mu}\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}C(s_1, s_0)\\C(s_2, s_0)\\\vdots\\C(s_n, s_0)\\1\end{bmatrix}\]where \(\hat{\mu}\) is the estimated mean of the variable, and the additional row and column of 1’s correspond to the constraint that the weights sum to 1 and the assumption that the mean of the variable is unknown. The weights \(\lambda_i\) are chosen to minimize the estimation variance subject to the constraint that they sum to one.

-

Simple kriging:

Simple kriging assumes that the mean of the unknown variable is known and that the covariance between the variable at any two locations depends only on the distance between the locations. The kriging system of equations for simple kriging can be written as:

\[\begin{bmatrix}C(s_1, s_1) & C(s_1, s_2) & \cdots & C(s_1, s_n)\\C(s_2, s_1) & C(s_2, s_2) & \cdots & C(s_2, s_n)\\\vdots & \vdots& \ddots & \vdots\\C(s_n, s_1) & C(s_n, s_2) & \cdots & C(s_n, s_n)\end{bmatrix}\begin{bmatrix}\lambda_1\\\lambda_2\\\vdots\\\lambda_n\end{bmatrix} = \begin{bmatrix}C(s_1, s_0)-\mu\\C(s_2, s_0)-\mu\\\vdots\\C(s_n, s_0)-\mu\end{bmatrix}\]where \(\mu\) is the known mean of the variable and the weights \(\lambda\) are chosen to minimize the estimation variance subject to the constraint that they sum to one.

-

Universal kriging:

Universal kriging assumes that the mean of the unknown variable can be modeled using a known function of the spatial coordinates and/or covariates (drift or trend term), such as a linear or quadratic function. The covariance between the variable at any two locations depends on depends only on the distance between the locations. The universal kriging estimator at an unsampled location \(s\) is given by:

\[Z(s) = \sum_{j=1}^{p} \beta_j v_j(s) + \delta(s) \quad\quad (7)\]where \(\beta_j\) are the coefficients of the drift term in the regression model, and \(v_j(s)\) is the value of the $j$th covariate at location \(s\).

The kriging system of equations for universal kriging can be written as:

where \(C(s_i, s_j)\) represents the covariance between locations \(s_i\) and \(s_j\) in the presence of a drift term, \(C(s_i,s_0)\) represents the semivariance between the unsampled location and location \(s_i\), \(\lambda_i\) represents the kriging weights for each sampled location, \(\mu\) represents the kriging estimate of the mean value, \(\beta_j\) represents the coefficients of the drift term in the regression model, and \(v_j(s_i)\) represents the value of the \(j\)th covariate at location \(s_i\).

Implementation

Fitting Semivariogram

The implementation example used in this task is based on the book “An Introduction to R for Spatial Analysis and Mapping” by Brunsdon and Combergstat R library in your R environment. The gstat library is designed for geostatistical modeling and spatial data analysis in R, providing a wide range of tools for spatial data exploration, variogram modeling, kriging, and spatial prediction.

We will be using the fulmar dataset included in the gstat library to practice kriging interpolation. The fulmar dataset contains airborne counts of the sea bird Fulmaris glacialis during August and September of 1998 and 1999 over the Dutch part of the North Sea. The counts are taken along transects corresponding to flight paths of the observation aircraft and are transformed to densities by dividing counts by the area of observation, which is \(0.5 km^2\).

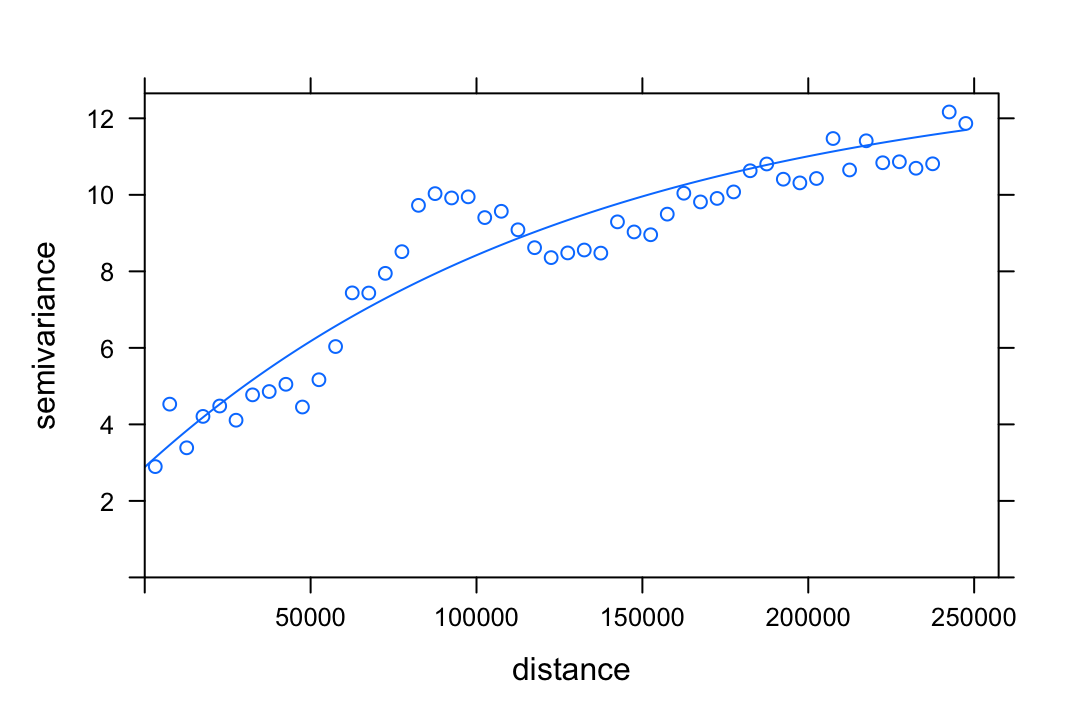

The codes below plots the kriging semivariogram of the fulmar dataset:

# Load the gstat library

library(gstat)

# Load the fulmar dataset from the gstat library

data("fulmar")

# Create a SpatialPointsDataFrame object from the fulmar dataset

# The cbind function combines the x and y coordinates into a matrix, which is used to create the SpatialPointsDataFrame

fulmar.spdf <- SpatialPointsDataFrame(cbind(fulmar$x,fulmar$y), fulmar)

# Calculate the empirical variogram of the 'fulmar' variable in the fulmar.spdf dataset

# The 'fulmar~1' formula specifies the variable to be analyzed and '1' indicates that there are no covariates

# The 'boundaries' argument sets the distance lags for the variogram calculation

evgm <- variogram(fulmar~1,fulmar.spdf, boundaries=seq(0,250000,l=51))

# Fit a variogram model to the experimental variogram

# The 'vgm' function specifies the type of variogram model to be used

# Here, a Matérn model with a sill of 3, a range of 100000 and a nugget of 1 is used

fvgm <- fit.variogram(evgm,vgm(3,"Mat",100000,1))

# Plot the experimental variogram with the fitted variogram model

# The 'model' argument specifies the fitted variogram model to be plotted

plot(evgm,model=fvgm)The variogram() function computes the empirical variogram, and takes the following key arguments:

-

formula: A formula specifying the variables to be used in the calculation of the variogram. The formula takes the formresponse~predictor, whereresponseis the variable to be analyzed andpredictoris an optional covariate or drift term. The covariate can be a numeric or factor variable, and the drift term can be specified as 1 forordinary kriging. -

data: A spatial data object containing the variables specified in the formula argument. -

width: The maximum lag distance between pairs of sample locations. If not specified, the function will determine the maximum lag distance based on the data.

Figure 1: Matérn Semivariogram of Fulmar Counts in the North Sea

Nugget

In vgm(3,"Mat",100000,1), the nugget argumaent refers to the intercept of the variogram at zero distance or lag. It represents the spatial variability that cannot be explained by the spatial autocorrelation in the data, such as measurement error or microscale variation.

The nugget effect is an important concept in variogram modeling because it affects the shape of the variogram and the spatial prediction derived from it. A large nugget effect indicates that there is a high degree of spatial variability at small distances or lags, which can lead to difficulties in spatial interpolation and prediction. On the other hand, a small nugget effect indicates that the spatial variability is primarily driven by spatial autocorrelation, making it easier to predict the value of the variable at unsampled locations.

Variogram models that account for the nugget effect can be used to estimate the spatial correlation structure of the data and to make predictions at unsampled locations based on that structure. Different types of variogram models, such as exponential, Gaussian, and Matérn, incorporate the nugget effect in different ways and may be more appropriate for certain types of data or spatial structures.

Running Kriging

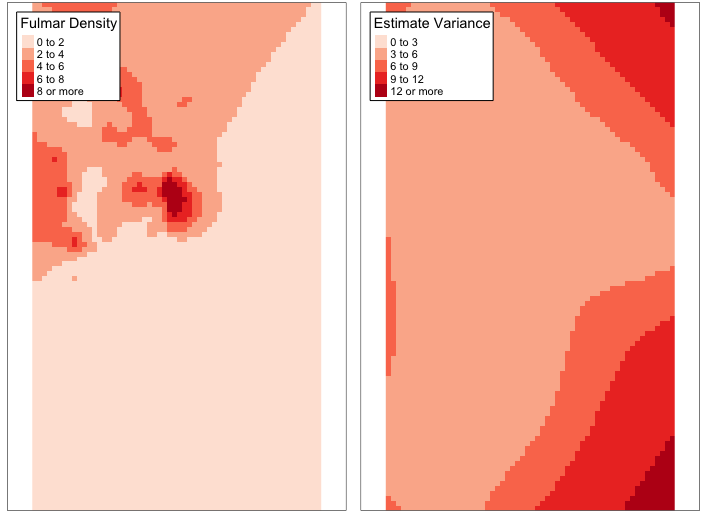

Now we can perform kriging interpolation using the variogram model. Run the following code:

s.grid <- spsample(fulmar.spdf, type = "regular", n = 6000)

krig.est <- krige(fulmar ~ 1, fulmar.spdf, newdata = s.grid, model = fvgm)This code creates a variogram model from the fulmar data and uses it to perform kriging interpolation on the s.grid object. The points at which estimates are made are supplied in s.grid. The krige() function returns a SpatialPointsDataFrame object containing the kriging estimates.

To create a choropleth map of the kriging estimates, we need to convert the kriging results to a SpatialPixelsDataFrame object and define a color palette for the map. We also need to define break values for the estimate variance map. Run the following code:

krig.grid <- SpatialPixelsDataFrame(krig.est, krig.est@data)

levs <- c(0, 2, 4, 6, 8, Inf)

var.levs <- c(0, 3, 6, 9, 12, Inf)Next, we can create the choropleth maps using the tmap package. Run the following code:

library(tmap)

krig.map.est <- tm_shape(krig.grid) +

tm_raster(col = 'var1.pred', breaks = levs, title = 'Fulmar Density', palette = 'Reds') +

tm_layout(legend.bg.color = 'white', legend.frame = TRUE)

krig.map.var <- tm_shape(krig.grid) +

tm_raster(col = 'var1.var', breaks = var.levs, title = 'Estimate Variance', palette = 'Reds') +

tm_layout(legend.bg.color = 'white', legend.frame = TRUE)

tmap_arrange(krig.map.est, krig.map.var)Figure 2: Kriging estimates of fulmar density (left) and associated variance (right)

This example use ordinary kriging. For performing simple kriging with a known mean, you can specify the beta argument in the krige() function to the mean, and the simulation will be based on simple kriging. YOu can also sepcified the trend coefficients (including intercept) for universal kriging by providing a vector here.